Last Friday I was able to return to the Denver Art Museum for another look at the current tapestry exhibit.

The show starts with large three historic tapestries.

The first is

Birth of the Prince of Peace. It was woven in an unknown Flemish workshop, probably in Tournai, in 1510 - 1530. It is an allegorical tapestry and here we see the new mother receiving her son (the prince of peace) from her attendant. The baby is difficult to see now as those yarns have faded in color in the five centuries since it was woven.

|

| Birth of the Prince of Peace (detail) |

Here is the whole piece being admired by the group from the American Tapestry Alliance who went for a tour.

|

| Birth of the Prince of Peace |

The second piece was a table covering called

The Five Senses, woven in England in 1610. It is the piece in the center between

Birth of the Prince of Peace to the left and

Village Festival to the right. In the photo below, Alison McCloskey and Stephania VanDyke are giving us a tour of the show.

They know this piece is a table cover because the images at the top of the piece are upside down. The detail below is of the sense of smell.

|

| The Five Senses (detail) |

The third of these old Flemish and English tapestries is

Village Festival which was woven at the Brussels workshop of Urbanus Leyniers from 1705 - 1747. It was based on the paintings of David II Teniers (Flemish 1610 - 1690).

This piece got 300 hours of restoration work and is about 9 by 20 feet. During this time period, poor quality silk was used and the parts of the tapestry that were silk (large parts of the sky, part of a pig, other parts that they wanted to be shinier), have largely disappeared. Alison McCloskey, the conservator who talked about this work, said that metals were added to silk at that time. The metals made the silk weaker and it breaks easily.

|

| Village Festival (I have also seen it called Peasant's Feast) |

Last spring I was able to see this piece being restored. There were bits of silk all over the floor under the frame they were using to do the stabilizing, like shiney snow. Fortunately the weft that was wool and the wool warp are intact.

This is the frame they used to restore the piece. It has two large rollers on each side and they can scroll through the tapestry as they work.

|

| Village Festival on restoration frame at the Denver Art Museum |

There were two conservators working on stabilizing this piece. They do not do any reweaving of areas. Alison told us that reweaving is invasive, yarns don't age in a compatible manner, and it is difficult to remove. In the photo below you can see the twining technique they use every few inches to connect the warps. The silk bits have mostly fallen out of this part of the tapestry and the warps are exposed.

|

| Village Festival, detail of restoration |

They use two strands of DMC embroidery floss for these stabilization twinings. Alison said that the floss is the right strength for the tapestry and it comes in such a wide variety of colors, they can match what they need so it disappears into the tapestry.

Here is a detail of

Birth of the Prince of Peace which I saw being restored a few months prior to

Village Festival. You can see the DMC floss. This tapestry, though a couple hundred years older, is in better shape. There are some old repairs and multiple slit sewings that had to be removed. The old repairs were either done in an orange color or the colors have changed in the intervening centuries. The conservation team did remove some of those old repairs especially in the faces of the figures where they were extremely distracting.

|

| Birth of the Prince of Peace, restoration in process |

The photo below shows a few of the old repairs in an orangish, thicker tapestry weave. They are the blotches that don't seem to fit. You can also see where the slits have been resewn repeatedly. Alison thought there were perhaps 20 different resewings over the 500 years this tapestry has been around. You can see more images of the restoration of these tapestries in

THIS POST.

|

| Birth of the Prince of Peace (detail of repairs) |

And what with all the drinking and merry-making, someone has to pee...

|

| Village Festival (detail) |

Though I find these old tapestries fascinating,

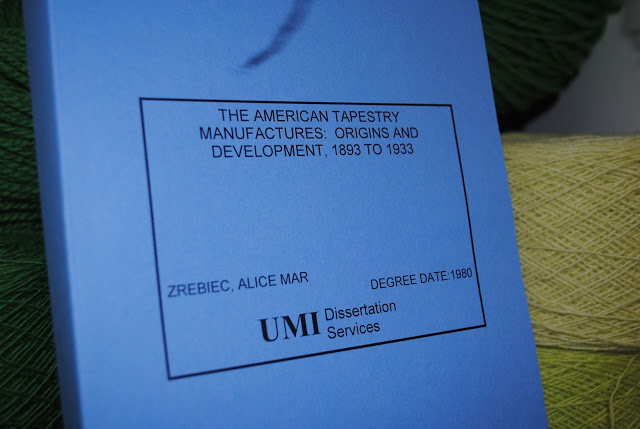

I fear we are in danger of thinking that tapestry is ONLY a historical practice and is irrelevant today. The tapestries in the rest of the show make us think about what tapestry has been over the last five centuries, how it has changed, and perhaps a little about what it means today. It would take an exhibit ten times this size to really explore these ideas, but Alice Zrebiec, curator, has made a good start in Creative Crossroads just with objects from the DAM collection.

Here are some overview photos from the exhibit followed by some more details.

|

| left to right: Josep Grau Garriga, Mark Adams, Irvin Trujillo, James Koehler, Ramona Sakiestewa |

|

| Irvin Trujillo, Saltillo Shroud (right), Don Leon Sandoval, Las Cinco Estrellas (left) |

Irvin Trujillo was at the opening dinner and he talked about this piece a little bit. You can see more photos from that night

HERE. Below is a detail of the work which is done in wool, silk, and metal thread. Irvin says that this piece is a tribute to the Mexican saltillo serapes and their influence on Rio Grande weaving in New Mexico. His father never wove in this form because he didn't want to acknowledge his Mexican heritage. Irvin says that this piece and the prominent center figure is a sort of "coming out" from the shame of his father. Also, there was that thing about pop biscuits.

|

| Saltillo Shroud (detail) |

There is a very large Navajo rug by Ason Yellowhair (1930 - 2012), woven in 1983. There is an interesting photo of Ason weaving another rug with her chair on top of her dining table so she could reach the weaving line on her traditional Navajo loom.

|

| Ason Yellowhair, Bird and Flower Pictorial Rug (detail) |

This massive piece that you see from all over the gallery was woven by Josep Grau-Garriga (Catalan, 1929 - 2011). He studied with Jean Lurcat in France and then returned to Spain where he became the director of the Catalan School of Tapestry. He took traditional tapestry into a sculptural form which, in this piece, was meant to be viewed in the round.

|

| Josep Grau Garriga, Tapis Pobre |

The very large,

Flight of Angels, designed by Mark Adams (1925 - 2006), was woven in 1962 by Paul Avignon in Aubusson, France.

|

| Mark Adams, Flight of Angels |

|

| Flight of Angels (detail) |

|

| Flight of Angels (detail); Mark Adams' signature with the atelier's mark |

Ramona Sakiestewa is an artist/weaver of Hopi heritage.

|

| Ramona Sakiestewa, Katsina 5 |

|

| Rebecca Bluestone, Four Corners/8, 1997 |

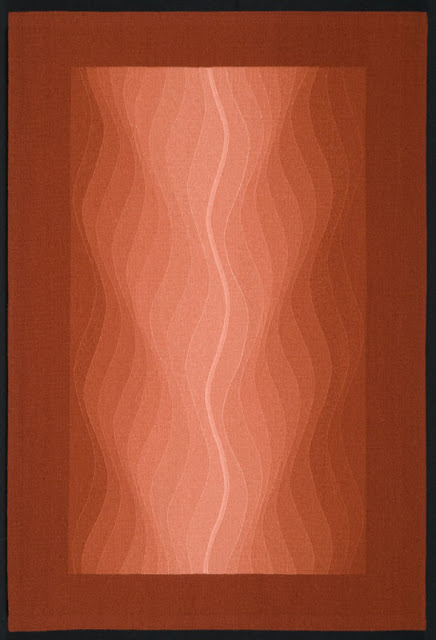

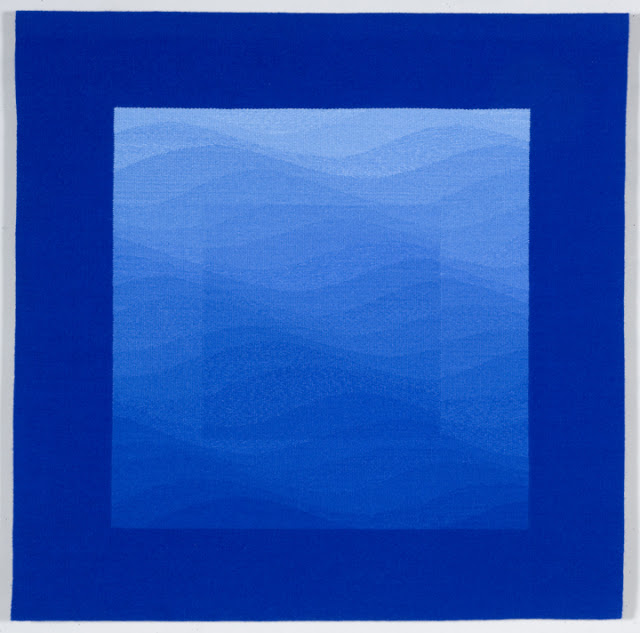

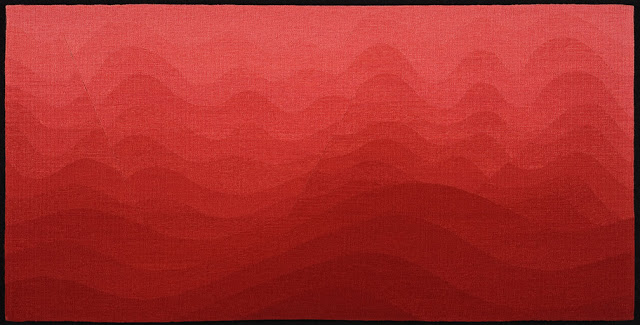

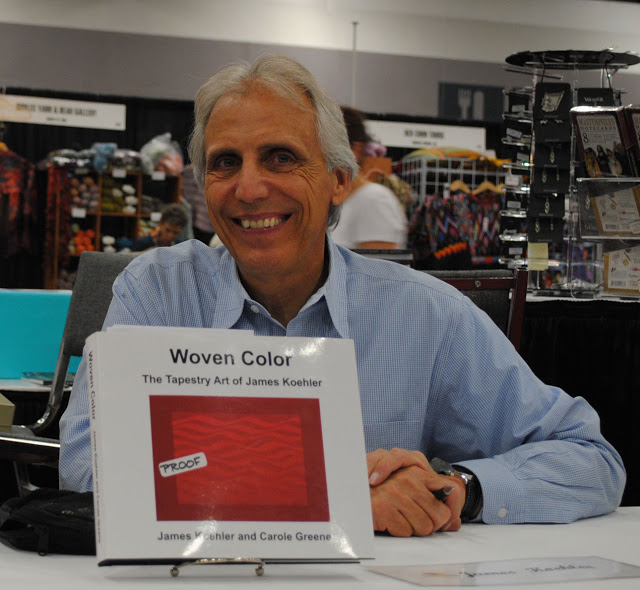

James Koehler had a piece in the show and you can see more photos as well as watch five videos the museum made about his work and practice

HERE.

There are many delightful surprises in this show. I hope you'll visit to see these in person as well as the ones I haven't shown you.

|

| Denver Art Museum to the left and the Denver Public Library straight ahead. |

Imagine 300 hours of this on just one piece?!!!